The Federal Circuit has issued its nonprecedential decision in In re Blue Buffalo Enterprises, Inc. affirming the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s (“Board”) rejection of several claims of U.S. Patent Application No. 17/136,152 as obvious. This alert summarizes the case background, the Federal Circuit’s reasoning, and key takeaways for patent practitioners including exercising caution in using the oft-preferred “configured to” claim language.

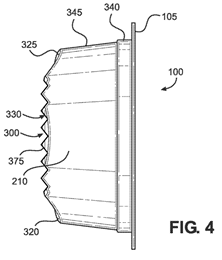

The ’152 application relates to a packaging container for wet pet food. The design, as shown in FIG. 4 of the ‘152 application below, includes a deformable sidewall that allows a user to squeeze food out of the container and a tool portion with projections formed on the bottom wall that breaks up or tenderizes food. Claim 1 recites that the sidewall is “configured to be readily deformable” and that the projections on the bottom wall are “configured for” breaking up or tenderizing food.

During prosecution, the Examiner rejected claims 1 and 3-12 as obvious over Coleman and other prior art. The Board affirmed and designated its affirmance as a new ground of rejection. Blue Buffalo appealed, challenging the Board’s interpretation of the terms “configured to” and “configured for.”

The Federal Circuit reviewed the Board’s claim construction de novo and affirmed. The Federal Circuit rejected Blue Buffalo’s argument that “configured to” should mean “specifically designed to.” In re Blue Buffalo Enterprises, Inc., Nos. 2024-1611 (Fed. Cir. January 14, 2026), at 4. Instead, it agreed with the Board that the terms “configured to” and “configured for” in this context simply mean “capable of.” Id. at 4-5.

The Federal Circuit distinguished Blue Buffalo from In re Giannelli and Aspex Eyewear explaining that those decisions interpreted the phrase “adapted to,” not “configured to.” Id. at 4. Additionally, the Federal Circuit noted that, in each case, the written description supported a narrower interpretation. Id. Here, the specification did not suggest that the sidewall and bottom wall projections were specifically designed for particular functions, but merely capable of performing them. Id.

Under this construction, Blue Buffalo conceded that it did not challenge the Board’s obviousness determination. Accordingly, the Federal Circuit affirmed the rejection of claims 1 and 3-12.

The Federal Circuit’s interpretation of “configured to” and “configured for” in In re Blue Buffalo aligns with the decision in ParkerVision, Inc. v. Qualcomm, Inc., where the Federal Circuit similarly declined to narrowly interpret functional limitations without explicit evidence.

Together, these decisions reinforce a few important points to keep in mind while drafting patent applications:

- Be precise with functional claim language. Terms such as “configured to” may be interpreted broadly to mean “capable of,” absent clear indications to the contrary in the specification such as narrowly defining the required operating conditions or structure.

- When possible, avoid “configured to” for key claim elements altogether. Instead, replace it with explicit structural limitations or operational requirements.

- Draft claims with obviousness in mind. If a functional limitation could encompass prior art devices that merely have the capability to perform a function, consider including structural limitations or explicit design features to avoid obviousness rejections.

If you have questions about this case, or would like help evaluating the impact of this decision on your patent portfolio or prosecution strategy, please contact a Dinsmore intellectual property attorney.